The Complete Patents of Nikola Tesla

Nikola Tesla, the "man who invented the twentieth century," was born July 10, 1856, at Smiljan, Lika province (in modern Croatia), a part of the expiring Empire of Austro Hungary. His father, Rev. Milutin Tesla of the Serbian Orthodox Church, intended Nikola for the priesthood, but did not insist it must have been hard to make demands of the high strung, fragile youth who was his son. On Nikola's evidence we know his mother, Duka Mandic, to have been an inventor, a maker of tools and devices for her weaving, carpentry, and other handiwork.

Nikola Tesla, the "man who invented the twentieth century," was born July 10, 1856, at Smiljan, Lika province (in modern Croatia), a part of the expiring Empire of Austro Hungary. His father, Rev. Milutin Tesla of the Serbian Orthodox Church, intended Nikola for the priesthood, but did not insist it must have been hard to make demands of the high strung, fragile youth who was his son. On Nikola's evidence we know his mother, Duka Mandic, to have been an inventor, a maker of tools and devices for her weaving, carpentry, and other handiwork.

As a child Nikola manifested a full share of Duka's ingenuity, building among other things a bug propelled engine. Much later he would mention that he had always the ability to see his ideas constructed in his mind, and in such detail that he could adjust and balance the parts. In school he absorbed languages quickly (English, French, Getman, Italian) and made an impressive showing in mathematics.

He entered the Polytechnic College of Graz in 1875, studied hungrily, but for lack of funds was unable to complete his second year. He took himself to Prague, immersing his restless mind in the university library there (and took up gambling as a means of support-with what success is uncertain); he returned to Smiljan in 1879.

Already at Graz he knew that electricity would be his life's fascination. Indeed, this was the scientific frontier, where mystery and knowledge collided. When he learned in 1881 that a telephone exchange, one of Europe's first, was to be built in Budapest, he left at once. The Edison Tel. Co. (European subsidiary) in Budapest hired him, sent him to Paris in 1882 and to other cities. His standing and repute within the field were sufficient by 1884 that a colleague wrote a letter recommending him to Thomas Edison. Tesla fully appreciated that an inventor's prospects in America to attract capital, to manufacture and sell, to reap rewards-greatly exceeded his opportunities in Europe.

He did emigrate and he did go to work for Edison, but for less than a year, until the fee promised for a particularly difficult project, redesign of an Edison dynamo, failed to materialize. Edison, it is recorded, made some mention of the Serb's failure to comprehend American humor. (Of course Tesla, who later formed a great friendship with Mark Twain, perfectly well understood American humor and Edison.)

Over the next ten years, free to make his own arrangements, Tesla consulted, invented, invested forming with his backers a number of companies and producing the forty or so fundamental AC patents that revolutionized the running of industrial America. His name became synonymous in the press with electrical wizardry; he was seldom photographed without megavolt streamers playing around him, the apparatus afire with an eerie glow. All of which is a fair picture of the man: he relished the highvoltage drama of his public demonstrations but no less in the lab insisted on being first and closest in any chancy experiment.

Tesla was" in any case, a natural showman. Strikingly thin, six foot four, always whitegloved and well dressed, he lived at the Waldorf (when he could afford it), ate the best food, with the best people, and infallibly charmed his company. But that problematic, intense youth never disappeared: he counted things compulsively, calculated the volumes of bowls and cups before he could eat from them; his assorted phobias and fetishes perhaps denied him any close relationships. He wrote of recurrent visual sensations, bright and geometric, which occasionally overwhelmed his sight, actually blotting out scenes in front of him.

Tesla was" in any case, a natural showman. Strikingly thin, six foot four, always whitegloved and well dressed, he lived at the Waldorf (when he could afford it), ate the best food, with the best people, and infallibly charmed his company. But that problematic, intense youth never disappeared: he counted things compulsively, calculated the volumes of bowls and cups before he could eat from them; his assorted phobias and fetishes perhaps denied him any close relationships. He wrote of recurrent visual sensations, bright and geometric, which occasionally overwhelmed his sight, actually blotting out scenes in front of him.

Among his business investors he would eventually number the likes of J. P. Morgan and John Jacob Astor, but the most important for his aspirations was an early association with George Westinghouse. Westinghouse purchased Tesla's basic AC patents in 1888 for cash and shares amounting to $60,000 and a royalty on electrical horsepower sold. (By agreement the two principals canceled the mostly unpaid royalty in 1897; the lump sum Westinghouse negotiated has never been firmly determined, though a check record for $216,000 does exist.) More importantly Tesla acquired a resourceful and tenacious champion in the Westinghouse Corporation.

A fierce, often underhanded competition raged for years between the General Electric Co. (a creature of Morgan) and Westinghouse. GE's strategy, when mere engineering would not avail, was to invent ghastly tales of AC hazards and misadventures. In 1890 the company went so far as to license, through an agent, the Westinghouse system in order to power a death contraption which they called an "electric chair." Sing Sing Prison, in upstate New York, was persuaded to use it, with the gratifying results for GE that the press for a while played headlines in which prisoners were "Westinghoused."

When the publicity battles were over, and the superiority of AC systems apparent, Westinghouse was kept constantly in the courts, defending the patents�which the company did with ferocity. For Tesla, now an eminence in the field, success brought little in the way of wealth. With consultant and contract work he lived comfortably enough and kept his lab busy; he sometimes wrote that genuine millions could not elude him for long.

Through the 1890s he absorbed himself (and his redoubtable chief assistant, George Scherff) in work with x�rays, with high�frequency, high�voltage phenomena, and with radio. By 1899 he had built in Colorado Springs an isolated laboratory in which he could unleash power at unheard�of levels. His "magnifying transmitter," which included a 52�foot Tesla coil, reached 12 Mv in the secondary-the arcs thrown from its antenna mast sounded a man�made thunder for miles around. As satisfying as were such spectacles for their creator, and tantalizing to his searching mind, any possible commercial value in energy at this scale lay far, far over the horizon.

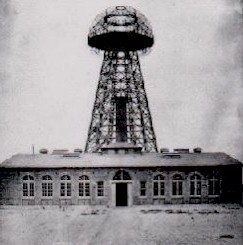

A 1902 venture, with J. P. Morgan, to construct a transatlantic radio installation (at Wardenclyffe, Long Island) was abandoned by 1906. Troubled from the outset by thinness of financing, the facility never became fully operational.

Now entering his fifties, Tesla received honors with regularity (including the Edison Medal) and stipends or fees enough to make ends meet, but clearly a decline had set in. Patent filings were fewer, lectures more seldom, his eccentricities more noticeable. Still, he seemed always able to find working capital, putting together the Tesla Ozone Co. in 1910 and later the Tesla Propulsion Co. (to produce his new and patented turbine).

His notes, letters, and patent filings bespeak a genius at work through his seventies, but a genius whose time is increasingly given over to feeding the pigeons of Manhattan, and to nursing the sick ones in his hotel room. When he died, January 7, 1943, in a world at war, the FBI showed up within hours to open his safe�though Tesla had become an American citizen in 1891, his many boxes and crates were put under seal and unaccountably turned over to the OAP (Office of Alien Property). Many were released in 1952 to the Tesla Museum in Belgrade, some have not resurfaced. His is a legacy of brilliance and enigma.

Remarkable by any standard, Tesla's 111 patents illuminate only his most purposive, practical work. As he often lamented, there just wasn't enough time to tame the racing of ideas in his head; so much had to be left incomplete. Some of the projects�for achieving ultra-high vacuum, a rocket engine design, experiments in directed beams and solar power�simply don't fit into the early twentieth century. His musings on ball lightning (he proposed an onionlike gaseous sphere of many charged layers) accord well with the most recent and satisfactory computer models. Frequently he was content to publish his findings without regard to priority or patentability: he introduced in this way the therapeutic method now called diathermy.

But the patent record is, as always, incontrovertible and precise. All inventors who wish to eat regularly must sooner or later become acquainted with the ordeals of the patent process. It will be useful to sketch the essentials of filing, using, and defending these peculiar grants.

To begin, a U.S. patent can be filed only by the inventor. Other nations, at different times in history, have allowed patents to whomever appeared first, treating the act of filing much like staking out a gold claim.

The application itself consists of five parts: petition (who is filing), oath (swearing to originality), specifications (how is it made, what it does), claims (what is new, important, and patentable about it), and drawings. A specialist, a patent examiner with expertise in one or several fields, studies the application and begins the often long, unpredictable process. The heart of the application lies in its specifications and claims.

Language describing a device's function or manufacture might later become crucial to making distinctions between it and a world of seemingly similar machines. Ordinary words (like "sever , "inclined," "adjacent") have judicial pedigrees and must not be used casually. And the result must be clear enough that a person skilled in the appropriate arts could construct a copy from the description.

Claims should be neither too broad nor too narrow-but they must stake out clearly the territory the inventor wants for his own. Up to twenty claims may be submitted with the basic filing fee; more claims mean more charges.

Tesla's patent claims, it will be noted, generally iterate one or two basic ideas but described in several ways: this is good patent form. There are no unusual requirements of the drawings, so long as they correspond well with the specifications. Tesla never sent actual models with any filing, though a skeptical examiner did visit once to have a look at his remote�controlled devices (No. 613,809). The Patent Office only occasionally insists upon working models, most famously for all applicants presenting perpetual motion machines. But then, the Patent Office for years used the same tactic to shoo away persons bearing drawings of flying machines.

Between the filing and the grant of a patent, a number of time � and paper�consuming things generally happen. The examiner will request clarifications, disallow various claims, point out errors, and give notice of "interference"�existence of applications by other inventors whose work and claims are very similar. (In the U.S. an interference may prompt an investigation to determine whose work has priority in actual fact, not merely in time of filing.)

Tesla and his lawyers submitted arguments to dissolve potential interferences in nearly every patent. Against an earlier radio patent by Wilson, for example, Tesla pointed out that his own four�circuit transmitter / receiver (No. 725,605) operated with two distinct frequencies, while Wilson's used only one, polarized in two planes. Similar distinctions were made to challenges on behalf of Fessenden, Cardwell, MacKaye, Hogg, and DeForest.

When all the changes are made, claims language negotiated, objections answered, the sheaf of correspondence concerning a single Tesla patent, the "patent wrapper," might run to fifty or eighty pages and thousands of dollars in legal fees.

With all of these matters settled, and with the examiner satisfied that the patent can be reduced to "constructive practice"-that it can actually be built�a patent may finally be granted. (Tesla had a great deal of difficulty convincing the Patent Office about a balloon-supported conductor in No. 645,576. The inventor clearly didn't care how his antenna arrived at a great elevation, but the examiner did.)

In many ways the woes of an inventor only begin with the patent's issue. The patent is, legally, a "negative right"; it does not grant a right to manufacture (which might infringe in the process on other patents), it merely assures the right of its holder to bring infringement suits in court�a hazardous and expensive privilege.

The court might look into the patent and perhaps decide its novelty is a mere improvement upon some earlier design, the work of a skilled mechanic but not original or ingenious enough to merit a patent. Or it may conclude the patent covers something altogether obvious. Worse, the patent might describe a device patented earlier, a fatal case of "anticipation." It may be the inventor hasn't been vigilant, allowing general borrowing of the patent or, conversely, that the patent hasn't been put to any practical use-either way the court will detect "abandonment" of the patent. In all of these cases the patent will not be sustained. (In granting a patent, the Patent Office makes no guarantees about its legal durability.)

The pivotal patent case concerning priority in radio (Marconi Wireless Telegraph Co. v. U.S., 320 U.S. 1) didn't work its way up to the Supreme Court until 1943, when some of the issues in question were nearly thirty years old. Tesla, it must be understood, was not a party to this suit.

Marconi v. U.S. had begun as an action to recover licensing fees from the government for its use of certain radio equipment during World War 1. Although Marconi Wireless had ceased to exist after 1919, its patents and other property having been absorbed by RCA, it reserved the right to pursue this litigation. The legal ghost that Marconi Wireless had become won a victory in the U.S. Court of Claims to the tune of $42,984.93, but only by the thinnest edge: survival of a single claim among the many in the patent. The government appealed to the Supreme Court.

In the course of its eighty�page decision, the Court found it necessary to rule on many points of law, procedure, and fact, including the facts, or history, of radio development. Its consideration relied heavily on what it named a radio communication system with "two tuned circuits each at the transmitter and receiver, all four tuned to the same frequency," by which it meant tuned antenna (output / input) and oscillator (signal / detector) circuits coupled by transformers in each piece of equipment. But this should not be confused with the four circuits of a later, more sophisticated Tesla patent (No. 723,188), in which two different frequencies are transmitted and received�to eliminate a degree of noise and (though the Patent Office contested the claim) to allow greater privacy of transmission.

A majority of the Court found, after tracing the lineage of radio through Maxwell, Hertz, Lodge, Tesla, and Crookes, the basic Marconi patent (No. 763,772, filed Nov. 1900) used nothing not already included in Tesla's earlier patent No. 645,576 (filed Sept. 1897), except for the presence in Marconi's design of an inductively tuneable antenna. (And the antenna element under discussion-Lodge's patent, No. 609,104-was bought from Lodge by Marconi.) The Court went on to note that Stone's radio patent (No. 714,756) completely anticipated Marconi's, antenna included. Stone, by the way, had always credited Tesla with the first basic, workable design, saying of his own patent it was "practically the same as that employed by Tesla" �but with the valuable refinements of a tuneable antenna and design adjustments to "swamp" parasitic oscillations in the transmitter.

Even the patent history of Marconi No. 763,772 showed serious blemishes: it had been rejected outright by the Patent Office and was only wrangled into being by persistent renewal and argument of Marconi's lawyers. With the facts thus marshalled, and observing that no amount of commercial success could save Marconi's patent, the Court held it invalid.

The decision was stunning, especially in view of the ease with which the Marconi patent had prevailed in earlier suits. In a 1914 case one federal judge found singular value in Marconi's use of a ground connection, and heaped praises on him as the indubitable inventor of radio. Nearly thirty years later, writing in dissent of Marconi v. U.S., justice Frankfurter would credit only Marconi with having the "flash," the stroke of genius, that unites disparate elements into a fundamentally new process or device. Yet he could not identify wherein Marconi's patent differed from those that had come before.

More than one judge has lamented the court's role as scientific referee, for it often has little in resources or temperament to give the job an assured performance. Utterly specious notions persisted for years, in and out of court, over such things as a ground connection-chaff thrown into the proceedings by lawyers hoping to add technical mystery and confusion. (There is a ground in all of Tesla's patent specifications, and in everyone else's equipment, too.)

Slowly, perhaps a little grudgingly, writers of scientific history have enlarged their paragraphs on the development of radio, giving Tesla the credit he is due. Surely, as the patents show, if that all�unifying "flash" came to any man, it was Nikola Tesla.

MOTORS & GENERATORS

Preface to AC Motor/Generator Patents 3

THE PATENTS:

(Filing date)��� (description) (pat. no.)

Mar. 30, 1886��� Thermo-Magnetic Motor #396,121 5

Jan. 14, 1886��� Dynamo-Electric Machine #359,7489

May� 26, 1887��� Pyromagneto-Electric Generator #428,05714

Oct. 12, 1887��� Electro-Magnetic Motor #381,968 17

Oct. 12, 1887��� Electrical Transmission of Power #382,280 26

Nov. 30, 1887��� Electro-Magnetic Motor #381,969 35

Nov. 30, 1887� Electro-Magnetic Motor #382,279 39

Nov. 30, 1887� Electrical Transmission of Power #382,281 44

Apr. 23, 1888� Dynamo-Electric Machine #390,414 48

Apr. 28, 1888� Dynamo-Electric Machine #390,721 52

May� 15, 1888� Dynamo-Electric Machine or Motor #390,415 56

May� 15, 1888� System of Electrical Transmission of Power #487,796 58

May� 15, 1888� Electrical Transmission of Power #511,915 64

May� 15, 1888� Alternating Motor #555,190 67

Oct. 20, 1888� Electromagnetic Motor #524,426 71

Dec.� 8, 1888� Electrical Transmission of Power #511,559 74

Dec.� 8, 1888� System of Electrical Power Transmission #511,560 77

Jan.� 8, 1889� Electro-Magnetic Motor #405,858 84

Feb. 18, 1889� Method of Operating Electro-Magnetic Motors #401,520 87

Mar. 14, 1889� Method of Electrical Power Transmission #405,859 91

Mar. 23, 1889� Dynamo-Electric Machine #406,968 94

Apr.� 6, 1889� Electro-Magnetic Motor #459,772 97

May� 20, 1889� Electro-Magnetic Motor #416,191 102

May� 20, 1889� Method of Operating Electro-Magnetic Motors #416,192�� 106

May� 20, 1889� Electro-Magnetic Motor #416,193�� 110

May� 20, 1889� Electric Motor #416,194�� 113

May� 20, 1889� Electro-Magnetic Motor #416,195�� 116

May� 20, 1889� Electro-Magnetic Motor #418,248�� 122

May� 20, 1889� Electro-Magnetic Motor #424,036�� 125

May� 20, 1889� Electro-Magnetic Motor #445,207�� 129

Mar. 26, 1890��� Alternating-Current Electro-Magnetic Motor� #433,700�� 132

Mar. 26, 1890��� Alternating-Current Motor � #433,701�� 135

Apr.� 4, 1890��� Electro-Magnetic Motor #433,703�� 138

Jan. 27, 1891��� Electro-Magnetic Motor #455,067�� 141

July 13, 1891��� Electro-Magnetic Motor #464,666�� 145

Aug. 19, 1893��� Electric Generator #511,916�� 148

TRANSFORMERS, CONVERTERS, COMPONENTS

Preface to Patented Electrical Components 157

THE PATENTS:

(filing date)��� (description) (pat. no.)

May�� 6, 1885��� Commutator for Dynamo-Electric Machines #334,823 159

May� 18, 1885��� Regulator for Dynamo-Electric Machines #336,961 161

June� 1, 1885��� Regulator for Dynamo-Electric Machines #336,962 165

Jan. 14, 1886��� Regulator for Dynamo-Electric Machines #350,954 169

Apr. 30, 1887��� Commutator for Dynamo-Electric Machines #382,845�� 172

Dec. 23, 1887��� System of Electrical Distribution #381,970�� 177

Dec. 23, 1887��� Method of Converting and Distributing

Electric Currents #382,282 182

Apr. 10, 1888��� System of Electrical Distribution #390,413�� 187

Apr. 24, 1888��� Regulator for Alternate-Current Motors����� #390,820�� 192

June 12, 1889��� Method of Obtaining Direct from

Alternating Currents #413,353�� 197

June 28, 1889��� Armature for Electric Machines

(Tesla-Schmid, co-inventors) #417,794�� 204

Mar. 26, 1890��� Electrical Transformer or Induction Device� #433,702�� 208

Aug.� 1, 1891��� Electrical Condenser #464,667�� 211

Jan.� 2, 1892��� Electrical Conductor #514,167�� 213

July� 7, 1893��� Coil for Electro-Magnets #512,340�� 216

June 17, 1896��� Electrical Condenser #567,818�� 219

Nov.� 5, 1896��� Man. of Electrical Condensers, Coils, &c.�� #577,671�� 222

Mar. 20, 1897��� Electrical Transformer #593,138�� 225

HIGH FREQUENCY

Preface to Patents in High Frequency 231

THE PATENTS:

(filing date) (description) (pat. no.)

Nov. 15, 1890��� Alternating-Electric-Current Generator #447,921�� 233

Feb.� 4, 1891��� Method of and Apparatus for Electrical

Conversion and Distribution#462,418�� 238

Aug.� 2, 1893��� Means for Generating Electric Currents #514,168�� 242

Apr. 22, 1896��� Apparatus for Producing Electric Currents

of High Frequency and Potential #568,176�� 245

June 20, 1896��� Method of Regulating Apparatus for

Producing Currents of High Frequency #568,178�� 249

July� 6, 1896��� Method of and Apparatus for Producing

Currents of High Frequency #568,179�� 254

July� 9, 1896��� Apparatus for Producing Electrical

Currents High Frequency #568,180�� 258

Sept. 3, 1896��� Apparatus for Producing Electric

Currents of High Frequency #577,670�� 262

Oct. 19, 1896��� Apparatus for Producing Currents of High

Frequency #583,953�� 266

June� 3, 1897��� Electric-Circuit Controller #609,251 269

Dec.� 2, 1897��� Electrical-Circuit Controller #609,245�� 275

Dec. 10, 1897��� Electrical-Circuit Controller #611,719�� 280

Feb. 28, 1898��� Electric-Circuit Controller #609,246�� 285

Mar. 12, 1898��� Electric-Circuit Controller #609,247�� 289

Mar. 12, 1898��� Electric-Circuit Controller #609,248�� 292

Mar. 12, 1898��� Electric-Circuit Controller #609,249�� 295

Apr. 19, 1898��� Electric-Circuit Controller #613,735�� 298

RADIO

Preface to The Radio Patents 305

THE PATENTS:

(filing date)��� (description) (pat. no.)

Sept. 2, 1897� System of Transmission of Electrical

Energy #645,576�� 307

Sept. 2, 1897� Apparatus for Transmission of Electrical

Energy #649,621 314

July� 1, 1898� Method of and Apparatus for Controlling

Mechanism of Moving Vessels or Vehicles #613,809 318

June 24, 1899� Apparatus for Utilizing Effects Transmitted

from a Distance to a Receiving Device

Through Natural Media #685,955 331

June 24, 1899� Method of Intensifying and Utilizing

Effects Transmitted Through Natural Media��� #685,953������� 338

Aug.� 1, 1899� Method of Utilizing Effects Transmitted

Through Natural Media #685,954 344

Aug.� 1, 1899� Apparatus for Utilizing Effects

Transmitted Through Natural Media #685,956������� 353

May� 16, 1900� Art of Transmitting Electrical Energy

Through the Natural Mediums #787,412 361

July 16, 1900� Method of Signaling #723,188 367

July 16, 1900� System of Signaling #725,605 372

Jan. 18, 1902� Apparatus for Transmitting Electrical

Energy #1,119,732�� 378

LIGHTING

Preface to The Lighting Patents 385

THE PATENTS:

(filing date)� (description) (pat. no.)

Mar. 30, 1885� Electric-Arc Lamp #335,786�� 387

July 13, 1886� Electric-Arc Lamp #335,787�� 392

Oct.� 1, 1890� Method of Operating Arc Lamps #447,920�� 397

Apr. 25, 1891� System of Electric Lighting #454,622�� 400

May� 14, 1891� Electric Incandescent Lamp #455,069�� 405

Jan.� 2, 1892�� Incandescent Electric Light #514,170�� 408

MEASUREMENTS & METERS

Preface to Patents for Measurement 6, Meters 413

THE PATENTS:

(filing date)�� (description) (pat. no.)

Mar. 27, 1891� Electrical Meter #455,068�� 415

Dec. 15, 1893� Electrical Meter #514,973�� 418

May� 29, 1914� Speed-Indicator #1,209,359�� 421

Dec. 18, 1916� Speed-Indicator #1,274,816�� 429

Dec. 18, 1916� Ship's Log #1,314,718�� 434

Dec. 18, 1916� Flow-Meter #1,365,547�� 437

Dec. 18, 1916� Frequency Meter #1,402,025�� 440

ENGINES & PROPULSION

Preface to Patents for Engines & Propulsion 447

THE PATENTS:

(filing date)�� (description) (pat. no.)

Jan.� 2, 1892� Electric-Railway System #514,972�� 449

Aug. 19, 1893�� Reciprocating Engine #514,169�� 452

Dec. 29, 1893�� Steam-Engine #517,900�� 456

Oct. 21, 1909�� Fluid Propulsion #1,061,142�� 461

Oct. 21, 1909�� Turbine #1,061,206�� 465

Sept. 9, 1921�� Method of Aerial Transportation #1,655,113�� 470

Oct.� 4, 1927�� Apparatus for Aerial Transportation #1,655,114�� 476

VARIOUS DEVICES & PROCESSES

Preface to Various Devices & Processes 487

THE PATENTS:

(Filing date)�� (description) (pat. no.)

June 17, 1896�� Apparatus for Producing Ozone #568,177�� 489

Feb. 17, 1897�� Electrical Igniter for Gas-Engines #609,250 ��493

Mar. 21, 1900�� Means for Increasing the Intensity of

Electrical Oscillations #685,012�� 496

June 15, 1900�� Method of Insulating Electric Conductors #655,838�� 500

Sept.21, 1900�� Method of Insulating Electric Conductors

(reissue of #655,838) #11,865�� 506

Mar. 21, 1901�� Apparatus for the Utilization of Radiant

Energy #685,957�� 512

Mar. 21, 1901�� Method of Utilizing Radiant Energy #685,958�� 517

Oct. 28, 1913�� Fountain #1,113,716�� 521

Feb. 21, 1916�� Vaivular Conduit #1,329,559�� 525

May�� 6, 1916�� Lightning-Protector #1,266,175�� 531

1994 by Barnes & Noble Inc.

Maybe you like it:

The design includes:

- Hearing Through Wires: Antonio Meucci - The True Father of Telephony

- "Earth Energy and Vocal Radio" Nathan Stubblefield

- "Endless Light" Dr. Thomas Henry Moray

The design includes:

- Harnessing electricity from the Earth: Neither is Schumann Resonance, nor is it known by Electromagnetism. It's The Sea of Energy in Which the Earth Floats

- Extracted from ordinary electricity by the method called “fractionation.”

- Reverse Tesla coil - "Back to Back" mechanism

- Combination of radiant energy and negative resistance to amplify electricity

- And many other plans for Free Energy.

Κατηγορίες:

Σχόλια